For much of history, yellow has been revered as the colour of the gods - sacred, eternal and imperishable. Ancient Egyptians believed that the skin and bones of their deities were made of gold, and for the classical world, yellow was a symbol of light from above, protection and prosperity.

Ochre, a rich, earth pigment, was humanity’s first yellow, used to colour cave paintings and to decorate bodies. Used for millennia, the mineral orpiment was known in the ancient world as the closest imitation of gold. Made from deadly arsenic, Egyptians used it as a cosmetic, and legend tells of Roman emperor Caligula extracting real gold from it.

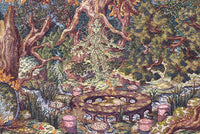

A manufactured version of orpiment became popular in the 17th century; known as King’s Yellow, the name came from Arabic alchemy, which describes the pigment and the mineral realgar as the ‘two kings’. Gamboge, another sulphide of arsenic harvested from trees, was used from the 8th century in China to paint illuminated manuscripts. Controversial Indian Yellow, made from the urine of cows fed only on mango leaves, was widely used in Europe from the 17th century but was banned in the 1800s.

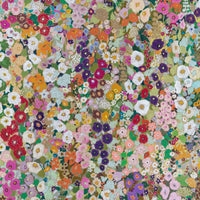

This gave way to the modern mineral pigments cadmium and chrome yellow, seen in the celestial constellations of Van Gogh’s Starry Night, Monet’s transcendent florals and George Seurat’s illuminating landscapes. It seems all that glitters is not always gold - sometimes it’s yellow.