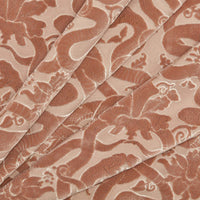

For Ancient Egyptians, green was the colour of regeneration and rebirth. They used the mineral malachite to decorate tombs for the dead and idols for the living. Through alchemy, the Greeks and Romans made verdigris by soaking copper plates in wine and the pigment was used to colour mosaics, frescoes and glass.

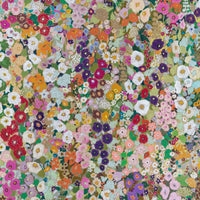

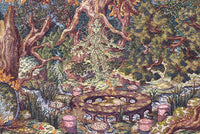

In the Middle Ages, where chivalry gave rise to courtly orchards and wreath rituals to welcome spring, green cemented its status as the colour of hope, youth and promise and was adopted by the mercantile classes, colouring robes of the gentry and precious illuminated manuscripts.

In the 18th century, after Madame du Pompadour declared her love for the colour by clothing herself and her home of Versailles in green, desire for the shade made its way through the classes. Chemists came up with a synthetic green that delivered vibrancy and longevity, but with it - death. Toxic arsenic gave a vivid green hue to paper, wall hangings and fabric and gained great popularity - but at a greater cost. It wasn’t until the 1960s that green pigment became completely safe, and once again claimed its place as a symbol of the healing power of Mother Nature, and all that she entails.